There are a range of online tools to assist managers in assessing risks to forests and woodlands and selecting appropriate adaptation measures.

Climate change is leading to warmer, drier weather conditions in spring and summer, and more frequent, prolonged droughts, which increases the risk of wildfires starting and spreading.

Wildfire risk also increases with disease outbreaks, windthrow damage, and changes to climatic suitability affecting vigour, which increase the level of standing and fallen deadwood and litter. According to the UK Climate Risk CCRA3 Wildfire Briefing, the risk of wildfire could double in a 2 °C global temperature-increase scenario and quadruple in a 4 °C scenario.

Wildfires are a semi-natural hazard, with most started accidentally from recreational or land management activities, or deliberately. Wildfires can start within forests or spread in from adjacent areas, such as grassland, heathland or moorland. Wildfires start more frequently in areas with high visitor numbers, near areas of socio-economic deprivation, and in areas close to public rights of way. Potential ignition sources include campfires, BBQs, hot oil or particles from machinery and vehicles, or power lines.

There are two periods of high wildfire risk: late winter-spring when there is dead-dry ground vegetation present (e.g., grass, bracken), overnight-frosts, dry periods with low daytime relative humidity; and summer, with hot and dry weather, including heatwaves and droughts. Wildfires during the latter are usually more intense and more damaging. The changing climate is likely to increase the risk of wildfires in both the late winter-spring and summer periods, and may extend the high-risk season into the autumn.

There are three main types of wildfires: surface fires, ground fires and crown fires. The most common is the surface fire, burning fuels such as heather, grass, bracken and gorse. Surface fires can burn fiercely, spread fast with long flames and at high fire intensity. There can be substantial growth of these fuels along roads and rides, before canopy closure, and after woods have been thinned. Ground fires consume peat and soil organic matter and threaten carbon stores. Smouldering peat fires are hard to extinguish and can re-kindle frequently.

Crown fires occur less frequently, during hot and dry summers, but are the most dangerous. They spread from surface fires, with ladder fuels, including tall shrubs, low tree canopies, standing deadwood and trees in poor health, and leaning windblown trees increase the risk of canopy fires.

Wildfires can have devastating consequences for people, property, industry, and the environment. The impacts of wildfires in forests are:

Economic – loss of tree stock and revenue, including ‘downstream’ industries such as wood processing, tourism and recreation. Disruption to transport, infrastructure and surrounding businesses.

Environmental – habitat and species loss, carbon loss, run-off, pollution, and smoke.

Social – health threats to forestry workers, visitors, and communities; disruption impacts on infrastructure, transport, and property.

Source: Building wildfire resilience into forest management planning – Forestry Commission Practice Guide

There are a range of online tools to assist managers in assessing risks to forests and woodlands and selecting appropriate adaptation measures.

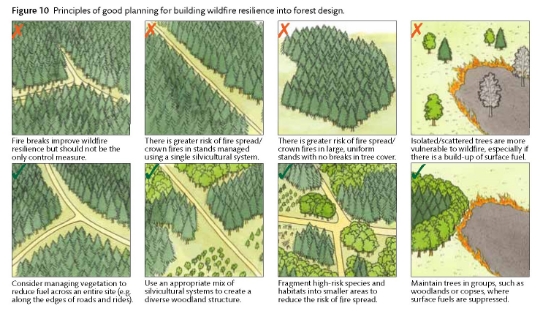

Risks from wildfire can be reduced through good practice in forest design, planning and operations. Wildfire resilience measures can address potential ignitions sources, fuel load, minimise wildfire spread, protect assets and support response. Wildfire hazards and risks should be considered when planning a new woodland, and resilience measures included in existing design plans.

For further information see Forestry Commission Practice Guide 22 Building wildfire resilience into forest management planning.

The adaptation measures listed below can help reduce the incidence and impact of wildfires in forests and woodland.

Discover how adaptation measures were selected following a 10-day forest fire in 2011.