Summary

Summary

Establishing a framework that places a value on carbon and thereby gives financial incentives for businesses and households to incorporate climate change impacts of their activities into their decisions is of key importance for the Government.

Valuing carbon is also important in comparing the relative merits of climate change mitigation activities over time.

Establishing a robust framework that values forestry carbon will be essential if the forestry sector is to be encouraged to play a greater role in helping to meet national carbon emission reduction commitments, and if significant opportunities for climate change mitigation by the sector are not to be missed.

Developing the Woodland Carbon Code in the UK is a potentially important step in providing a surer foundation upon which such a framework could be based.

Summary of the research, findings and recommendations (PDF-212K)

Review

A review of approaches to carbon valuation, discounting and risk management (along with a review of approaches to carbon additionality) have been undertaken to help inform the development of the above code of practice:

Publications

Report on carbon valuation in forestry and prospects for European harmonisation

Background to the need for carbon valuation

The impact of greenhouse gases (GHGs)

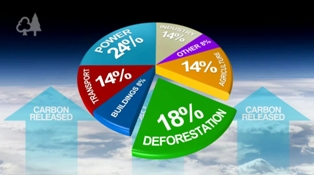

Increasing atmospheric concentrations of ‘greenhouse gases’ (GHGs), of which carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most important, is a primary cause of anthropogenic (human-made) climate change.

The global atmospheric CO2 concentration has risen by over a third from pre-industrial levels of about 280 ppm in 1750 to 406ppm in 2018, far exceeding the maximum of the natural range over the past 650,000 years of 300 ppm. Some recent estimates (GCP, 2020) indicate that the global atmospheric CO2 concentration is currently rising at over 2ppm a year. Aggregate atmospheric GHG concentrations (including gases such as methane and nitrous oxide), often measured in carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e), currently exceed 450ppm CO2e (EEA, 2019).

Human activities to date are estimated to have caused a global temperature rise by around 1 °C above pre-industrial levels. If warming continues at its current rate, global temperatures are expected to rise to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels by between 2030 and 2052. For global warming to be limited to 1.5 °C with no (or limited) overshoot, a reduction of around 45% in global net zero CO2 emissions will be needed by 2030, with global net zero CO2 emissions needed by around 2050 (IPCC, 2018).

Establishing a target stabilisation level

As the impacts of warming associated with different atmospheric concentrations of GHGs are uncertain, the target stabilisation level depends on a balance of expected probabilities and attitudes to risk. To avoid dangerous climate change, the UK and other signatories to the Paris Agreement (FCCC, 2015) committed to adopting policies consistent with holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. There has been a growing international consensus that limiting global average temperature increase to 1.5 °C is more consistent with limiting risks of dangerous climate change to an acceptable level, than 2 °C warming (e.g. IPCC, 2018).

In the absence of additional efforts to reduce emissions, ‘Business as usual’ could lead to an atmospheric concentration of between 750ppm and over 1300ppm CO2e by 2100. This could potentially lead to a temperature rise of 7 °C or more above pre-industrial levels (Stern Review, 2006, Box 8.1, p.220; IPCC, 2014).

In 2019 the UK became the first major economy to commit to bringing all its GHG emissions to net zero by 2050 (DBEIS, 2019a). A number of other countries also have committed to reaching a net zero emissions target by 2050, or in some cases, earlier (CCC, 2019, Table 2, p.22). For example, Scotland has adopted a target of net zero emissions by 2045. Pledges so far by signatories to the Paris Agreement are viewed as consistent only with limiting warming to around 3 °C by 2100 (CCC, 2019). A crucial international climate change conference (COP26) is expected to be hosted in the UK in 2021.

The impact of higher temperatures

With higher temperature increase, comes more severe impacts and a greater likelihood of exceeding critical thresholds. For example, instability of the marine ice sheet in Antarctica and irreversible loss of the Greenland ice sheet could be triggered at around 1.5 °C to 2 °C of global warming, which would lead to global sea level rise of several metres (IPCC, 2018).

If mitigation measures are only gradually introduced, we might be facing a 5% probability of a greater than 10 °C change in mean global surface temperature and a 1% probability of a greater than 20 °C change in around the next 200 years compared to pre-industrial revolution levels (based on data from scientific papers covered by the IPCC (2007, Table 9.3). Weitzman (2009) notes that in either case such rapid warming would lead to mass extinctions and biosphere ecosystem disintegration, destroying life on Earth as we know it.

Carbon valuation: references

- DBEIS (2019a): UK becomes first major economy to pass net zero emissions law. Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, London.

- DBEIS (2019b): Valuation of energy use and greenhouse gas. Supplementary guidance to the HM Treasury Green Book on Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government. Data tables 1 to 19: supporting the toolkit and the guidance. Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, London.

- DECC (2009): Carbon Valuation in UK Policy Appraisal: A Revised Approach. Department of Energy and Climate Change, London.

- Donofrio, S., Maguire, P., Merry, W., and Zwick, S. (2019): Financing Emissions’ Reductions for the Future State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2019. Ecosystem Marketplace, Washington DC, USA.

- EEA (2019): Atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations. European Environment Agency, CSI 013, CLIM 052, 5th Dec 2019.

- FC (2020): Woodland Carbon Guarantee. Forestry Commission, 4th Nov 2019 (15th Jan 2020 update).

- FCCC (2015): Adoption of the Paris Agreement. UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Conference of the Parties, 30th Nov to 11th

- GCP (2020): Trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide. Global Carbon Project, 7th Jan 2020 update.

- HM Treasury (2018): The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation.

- HM Treasury & DECC (2012): Valuation of energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Supplementary guidance to the HM Treasury Green Book on Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government. HM Treasury & Department of Energy and Climate Change, London.

- IPCC (2007): Climate Change 2007: The Physical Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC (2014): Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change, Working Group III Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC (2018): Global Warming of 1.5 °C: An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Stern, N. (2009): A Blueprint for a safer planet: How to manage climate change and create a new era of progress and prosperity. Bodley Head, London. ISBN 9781847920379

Related papers are available from the Grantham Institute - Stern, N. (2006): The Economics of Climate Change, HM Treasury / Cambridge University Press.

- Weitzman, M. (2009): On Modeling and Interpreting the Economics of Catastrophic Climate Change. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(1),1-19.

Current (2020) relationship between social value of carbon and market price

Summary

There is generally little relationship between the value to society of reducing greenhouse gas emissions or sequestering carbon and the market price at present. This is due to low emission reduction targets being set by governments in establishing cap-and-trade schemes and shortcomings in the design and operation of such markets as described below.

Carbon market prices are lower than social values

Market prices for carbon tend to be lower than social values. Prices in voluntary carbon markets worldwide are reported to have ranged from around $1/tCO2e to $47/tCO2e ($4/tC to $182/tC) in 2008, illustrating the importance of differences of quality and type. In 2018, projects in forestry and land use sectors accounted for the largest volume of carbon units sold in voluntary markets (50.7 MtCO2e), with the highest average prices ($8/tCO2e) reported for improved forest management projects (Donofrio et al., 2019).

Forest carbon covered by government quality assurance scheme

In 2010 the Forestry Commission launched a Woodland Carbon Code (https://woodlandcarboncode.org.uk/) to help underpin the quality of carbon units and confidence in the emerging market for carbon from UK forest projects. This provides a consistent approach to accounting for the carbon sequestration benefits of new woodland creation projects. 266 projects had been registered under the Woodland Carbon Code as of 31st March 2019 which were projected to sequester a total of 6.2 MtCO2e over their 100-year lifetime.

In late 2019 the government in England launched a £30 million Woodland Carbon Guarantee fund to support woodland creation in England. This will be done through the purchase of Woodland Carbon Units from projects validated and verified under the Woodland Carbon Code, with carbon prices to be determined by auction (FC, 2020).

Potential double-counting issues

Sale of carbon units by sectors covered by binding national or international carbon reduction commitments (e.g. mandatory reporting of emissions from land use activities under the Kyoto Protocol) gives rise to potential double-counting issues that can undermine their market value. Mechanisms do not currently exist to ensure the reporting additionality of any voluntary carbon units issued by the UK forestry sector by excluding them from national reporting, or allowing equivalent carbon credits to be retired.

Current (2020) UK government guidance on the social value of carbon

Current UK government guidance (DBEIS, 2019b) on what social values to apply in policy appraisal and how to apply them includes central estimates for 2020 of:

- £14/tCO2e (£51/tC) for sectors covered by the EU Emissions trading scheme (ETS) and

- £69/tCO2e (£254/tC) for non-ETS sectors

- Both are set to rise over time to £355/tCO2e (£1303/tC) in 2075-2078 at 2018 prices, thereafter declining.

The guidance is based upon a ‘target consistent’ approach which takes account of the marginal abatement cost required to reach a specified emissions’ reduction target (DECC, 2009). Values were initially estimated based upon target reductions of 34% compared to 1990 levels by 2020 and 80% by 2050, considered consistent with the UK’s contribution to limiting global temperature increase to 2 °C above pre-industrial levels (HM Treasury & DECC, 2012). Recent adoption of a net zero emissions target by 2050 could affect future guidance.

The effect of applying Treasury Green Book (declining) discount rates (Treasury, 2018) is shown in the table below for selected years, illustrating how present values of future benefits in non-ETS sectors (for example; what a tonne of CO2 sequestered by a forest in a future year is estimated to be worth currently) initially declines to 2030, before increasing to a peak in 2052-57, thereafter declining again.

Table: Social Values of carbon (£/tCO 2e at 2018 prices)

| Year | Sectors covered by EU ETS | Sectors not covered by EU ETS | ||||

| Central Price of Carbon | Discounted Price of Carbon | Index (2020 Discounted Price =100) | Central Price of Carbon | Discounted Price of Carbon | Index (2020 Discounted Price =100) | |

| 2020 | 14 | 14 | 100 | 69 | 69 | 100 |

| 2030 | 81 | 57 | 414 | 81 | 57 | 83 |

| 2040 | 156 | 78 | 566 | 156 | 78 | 113 |

| 2050 | 231 | 82 | 594 | 231 | 82 | 119 |

| 2060 | 307 | 81 | 588 | 307 | 81 | 118 |

| 2070 | 348 | 69 | 495 | 348 | 69 | 99 |

| 2080 | 353 | 52 | 374 | 353 | 52 | 75 |

| 2090 | 338 | 37 | 266 | 338 | 37 | 53 |

| 2100 | 309 | 26 | 186 | 309 | 26 | 37 |

The impact of tighter targets

Were tighter targets to be adopted (e.g. due to: accelerating global emissions; more severe than anticipated impacts; greater likelihood of catastrophic impacts; or a desire for greater certainty that critical thresholds will not be exceeded), the estimates of the social value of carbon would need to be revised upwards.

Estimating the social value of carbon

The different approaches

Valuing carbon is complex and uses different approaches according to whether a societal or market perspective is taken. Estimating the value of carbon from a societal perspective can be based on:

- The marginal damage cost of emissions – also termed the ‘social cost of carbon’ (SCC) –, or

- The marginal abatement cost (MAC) of reducing emissions or sequestering carbon, or

- The carbon price or pollution tax required to meet a given climate stabilisation goal.

A wide range of estimates of the social value of carbon exists, spanning at least three orders of magnitude from zero to over £1000/tC, and reflecting different methods, assumptions, models, and uncertainty concerning future impacts.

Early emissions’ reductions

These allow more time to avoid ‘dangerous’ climate change if impacts are worse than expected. These benefits have not been taken into account in valuing carbon.

Were they accounted for, adopting a declining present value of carbon over time (as initially the case with the discounted values under current UK government guidance) may be preferable to a constant (or increasing) value over time.

Downloads

forests_and_carbon_valuation_discounting_and_risk_management-5

Reviewing methods to value carbon over time, examining approaches for dealing with risk and considering approaches that could be used in extending standards to forestry more generally in voluntary carbon markets in the UK.

forests_and_carbon_valuation_discounting_and_risk_management

Reviewing methods to value carbon over time, examining approaches for dealing with risk and considering approaches that could be used in extending standards to forestry more generally in voluntary carbon markets in the UK.

forests_and_carbon_valuation_discounting_and_risk_management-2

Reviewing methods to value carbon over time, examining approaches for dealing with risk and considering approaches that could be used in extending standards to forestry more generally in voluntary carbon markets in the UK.

forests_and_carbon_valuation_discounting_and_risk_management-3

Reviewing methods to value carbon over time, examining approaches for dealing with risk and considering approaches that could be used in extending standards to forestry more generally in voluntary carbon markets in the UK.

forests_and_carbon_valuation_discounting_and_risk_management-4

Reviewing methods to value carbon over time, examining approaches for dealing with risk and considering approaches that could be used in extending standards to forestry more generally in voluntary carbon markets in the UK.

the_eu_emissions_trading_system_opportunities_for_forests

Brief research summary including background, objectives, methods, findings and recommendations.

forests_and_carbon_valuation_discounting_and_risk_management-1

Reviewing methods to value carbon over time, examining approaches for dealing with risk and considering approaches that could be used in extending standards to forestry more generally in voluntary carbon markets in the UK.