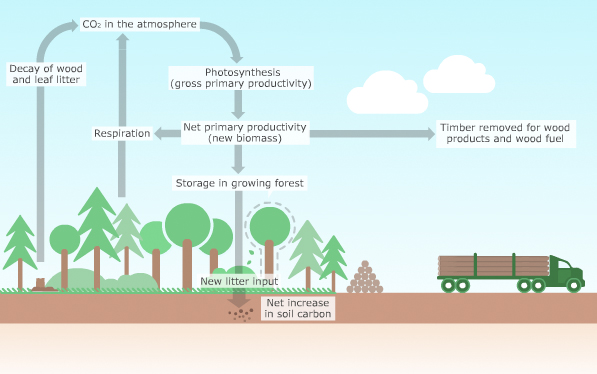

Figure 4.1 shows a forest’s contribution to the carbon cycle. Trees absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and release it through respiration; the difference is new biomass. Some of this biomass is dropped to the forest floor as litter (foliage, deadwood, etc), which in due course decays and is either released back to the atmosphere or becomes part of soil carbon. The remainder accumulates as increment in the forest, mostly as stemwood, branches or roots. A proportion of this accumulated biomass is harvested, for wood products or fuelwood; the rest is a net addition to the biomass stored in the forest.

Figure 4.1 Carbon Cycle

Sources chapter: UK Forests and Climate Change