Present in United Kingdom

Reportable – see ‘Report a sighting’ below

Scientific name – Aproceros leucopoda

The elm zigzag sawfly (Aproceros leucopoda) is a pest of elm trees (trees in the Ulmus genus). Its larvae (caterpillar-like grubs) feed on elm leaves and, in large numbers and the right environmental conditions, they can severely defoliate trees. This defoliation can be detrimental to the trees’ health and to other foliage-feeding invertebrate species which depend on elm trees.

It gets its common name from the characteristic zigzag pattern which the young larvae make on the leaves as they feed, as portrayed in the picture above.

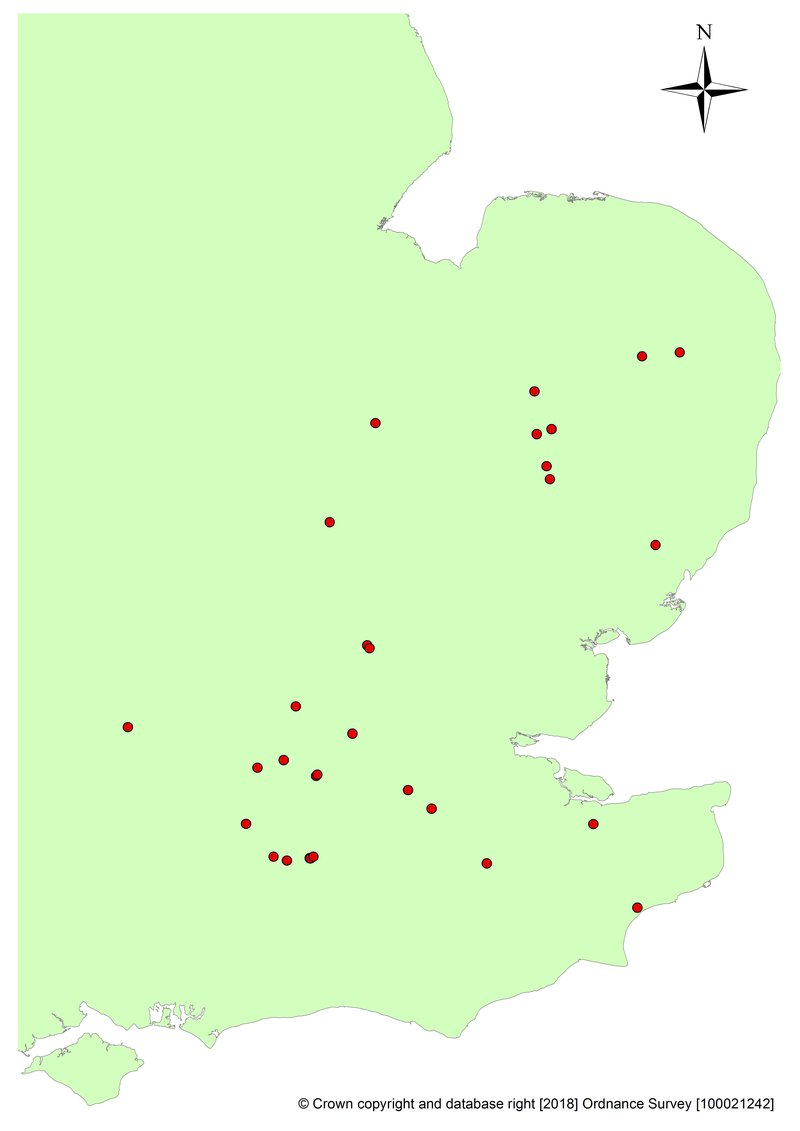

Elm zigzag sawfly is a native of eastern Asia which is now found in many parts of Europe. In the United Kingdom it has been reported from South-East England and the East Midlands of England, and it could spread further. The map below shows known locations of the pest in Great Britain based on reports submitted to Forest Research as of July 2018.

This pest specialises on elms, and appears to feed on all three elm species commonly found in Britain: English elm (Ulmus procera), wych elm (U. glabra) and field elm (U. minor).

Elm populations have not recovered from the introduction of Dutch elm disease, but those that remain in hedgerows and field margins still support a large diversity of insects, most notably the rare white-letter hairstreak butterfly (Satyrium w-album) and white-spotted pinion moth (Cosmia diffinis). Elms therefore remain an ecologically important species.

Elm zigzag sawfly has the potential to become a serious competitor of other elm foliage-feeding species, but trying to predict the amount of damage it will do in Britain is difficult. In some areas of Europe, the sawfly has been reported to have caused severe defoliation (74-98%), or even complete defoliation, but in other countries, such as Bulgaria, defoliation rates appear to be much lower (1-2%).

Britain has a cooler climate than the parts of continental Europe where significant defoliation has been recorded, and it might be that the sawfly’s life cycle will be slower here, and populations less damaging.

There are no records of trees being killed by the sawfly, although severe defoliation might lead to some dieback of shoots and branches.

The larvae are tiny green caterpillars with a characteristic habit of holding on to the inside edge of the leaf tissues as they feed (top picture). Young larvae are a near-uniform green and are easy to find if they are present within a zigzag track.

Older larvae have a lateral stripe on each side of their head capsules which crosses their eyes, and their second and third pairs of true legs have a brown, sometimes incomplete, T-shaped mark.

Symptoms of larval presence – Starting from the outside the leaf, the young larva begins to feed towards the central leaf vein, winding its way sinuously between the leaf veins. The easiest way to identify the pest is therefore to look for the characteristic zigzag or meandering-river pattern of the leaf damage (below) which the young larvae make as they feed in spring and summer. These patterns are made between the leaf veins. The identification can then be confirmed if one or more larvae can be found in association with the distinctive damage.

However, identifying the pest by the damage it causes becomes more difficult as the larvae get older. The width of the feeding trace increases as the larva grows. Eventually the larva stops, and moves back towards the outer edge of the leaf to the next leaf vein intersection, where it begins to feed in a more ‘normal’ leaf-chewing fashion, without the original zigzag. Feeding by older larvae can therefore obliterate the tell-tale zigzag patterns made by younger larvae. The traces can therefore look similar to the feeding damage caused by other leaf-chewing species, as in the picture below and, indeed, some of the damage might be caused by other leaf-chewing species which might also be present.

It is unlikely that there will only be one elm zigzag sawfly feeding trace on a tree, so if in doubt take the time to look for more feeding traces to see whether any better fit the expected pattern.

When fully grown, the larva leaves the feeding trace and wanders a short distance to find a secure place to pupate.

Pupae – After spinning a lattice-like, silken cocoon, the larva moults into a pupa before undergoing ecdysis and becoming an adult. Although an isolated pupa would be difficult, if not almost impossible, to identify as an elm zigzag sawfly pupa, a pupa within a lattice-like cocoon (below) on the underside of an elm leaf is almost certainly of this species.

The adult is a tiny, black, wasp-like sawfly with whitish legs (below). It is less than 1 cm (0.4 in) long, so it is rarely seen. It is also difficult for non-experts to identify, and even exerts need a microscope. Upon finding a suspected adult, check nearby for elm trees, and look for the feeding traces of larvae, or pupal cocoons. The sawfly in this picture is ovipositing (laying eggs).

We welcome reports of suspected sightings of elm zigzag sawfly to help us monitor its distribution and impacts.

Note that TreeAlert and TreeCheck both require photographs to be uploaded.

The pest could spread short distances at a time through the adults’ flight, and by the wind.

Longer-distance spread of the adult sawflies in or on vehicles is possible. There is evidence of spread along major arterial roads in continental Europe, with populations reported in elm trees at some motorway service stations. The discovery of outbreaks in Europe which are long distances from the nearest known populations also suggests this ‘jump spread’ by ‘hitch-hiking’ adult sawflies.

Long-distance spread could also occur in the transportation and importation of elm plants for planting. In this case, the pest is likely to be moved in the form of pupae in tiny cocoons a few millimetres long in the leaf litter and soil in the plant pots.

In England, the first adult sawflies of the year probably emerge from their pupation cocoons about April. The species is parthenogenetic, that is, they are all females, and mating with males is not necessary to reproduction. They lay eggs into the serrations at the edge of elm leaves. Larvae hatch from the eggs within 4-8 days.

The larvae proceed to feed on the leaf tissues between the main leaf veins. They pass through 4-7 instars (growth stages) in about 15-18 days, and then build either a loose silk cocoon on the underside of a leaf or, later in the year, a stronger, solid-walled cocoon that will protect the pupa over the winter.

The adult sawflies emerge from the cocoon within 4-7 days during the summer. At higher temperatures, e.g. 24 degrees centigrade, the life cycle is completed in 23-24 days, but at lower temperatures it takes longer. For example, at 11 degrees complete development requires 85 days.

Multiple generations are produced during the summer, although we do not know yet how many generations the sawfly might be able to complete in a year in the British climate.

Elm zigzag sawfly has not yet caused high levels of defoliation in Britain, but as its population builds up this situation might change. The most effective measures are:

Pesticide treatments have proved an effective means of controlling the larvae in other countries. However, the pesticides available for use in the UK are not specific to the sawfly larvae, and will kill other insect species. Therefore, pesticide applications are likely to have significant effects on other invertebrates inhabiting the elm trees.

Treated trees will almost certainly be re-infested from nearby populations, making repeat applications necessary. Use of chemical control is therefore likely to be limited to the protection of individual elm trees, or groups of elm trees of landscape, amenity or cultural importance.

The impact of predators and parasitoids is also largely unknown, and there are very few observations of predation on the sawfly’s larvae or pupae. The parasitoid fauna associated with the sawfly is therefore poorly understood, and further research is needed before any potential for control by natural means, such as predators and parasites, can be known.

Elm zig-zag sawfly is a native of Japan and parts of China. It has spread to Europe in recent decades, most likely with imported plants for planting.

It was first recorded in Europe in 2003, in Poland and Hungary, and has since been found in several other European countries, including Belgium and the Netherlands. As of 2018 it had not been confirmed in our nearest neighbour, France.

Evidence for its presence in Great Britain was first identified in 2017, in Dorking in the county of Surrey in southern England. Confirmation of its presence and further reports came from a wide area of South-east England and the East Midlands during 2018. The full extent of the sawfly’s distribution here is not yet known, but it is expected that it will continue to spread.

Exactly how the sawfly was introduced to Great Britain is also unknown. Natural spread across the English Channel seems unlikely for such a small insect, but it is possible. Human-assisted movements, for example, in or on vehicles, and with elm plants imported for planting, might also have played a part.

The current known distribution of elm zigzag sawfly in Britain is based on reports submitted to Forest Research.