Summary

November 2019

Phyto-threats workshop November 13th 2019, APHA, Sand Hutton, York

Phyto-threats project team meeting

November 14th 2019, APHA, Sand Hutton, York

November 2018

Phyto-threats project team meeting

November 20th 2018, Forest Research Northern Research Station, Roslin

June 2018

June 19-20th 2018, Stoneleigh Park, Warwickshire

April 2018

Phyto-threats project team meeting

April 26th 2018, CEH, Wallingford, Oxfordshire

October 2017

Phyto-threats project team meeting

October 3rd 2017, APHA, Sand Hutton, York

Reducing Phytophthora in trade and designing effective accreditation

Phyto-threats workshop

October 4th 2017, APHA, Sand Hutton, York

June 2017

June 20-21st 2017, Stoneleigh Park, Warwickshire

May 2017

Phyto-threats project team meeting

May 4th 2017, James Hutton Institute (JHI), Invergowrie, Dundee

March 2017

Phyto-threats attendance at the 8th Meeting of the International Union of Forest Research Organisations Working Party (IUFRO) 7.02.09, Phytophthora in forests and natural ecosystems

18-25th March 2017, Sapa, Vietnam

January 2017

28th USDA Interagency Research Forum on Invasive Species

10-13 January 2017, Annapolis, Maryland, USA

October 2016

Phyto-threats biannual all project team meeting

5 October 2016, APHA, Sand Sutton, York

Improving nursery resilience against threats from Phytophthora

Phyto-threats workshop

6th October 2016, APHA, Sand Hutton, York

April 2016

Phyto-threats start-up meeting

21st April 2016, NRS, Scotland

Phyto-threats workshop November 2019

November 13th 2019 held at APHA, Sand Hutton, York

Phytophthora disease threats in UK nurseries and wider landscapes: what’s here, what’s coming and what we can do about it

PHYTO-THREATS is a collaborative research project involving seven participating institutions from across Britain and is funded by the Living With Environmental Change partnership through the Tree Health and Plant Biosecurity Initiative. It ran from April 2016 till the end of December 2019. The four main objectives of the project are to;

- Examine the distribution, diversity and community interactions of Phytophthora in UK plant nursery systems

- Provide the scientific evidence to support nursery accreditation to mitigate further spread of Phytophthora

- Identify and rank global Phytophthora risks to the UK

- Gain a greater understanding of the evolutionary pathways of Phytophthoras

Sarah Green (Forest Research), Phyto-threats project co-ordinator, welcomed everyone and gave a brief introduction to the project, reiterating the aim to address global threats from Phytophthora species and to mitigate disease through nursery best practice. She described the outcomes of the previous two stakeholder workshops (in 2016 and 2017) in terms of evolving attitudes towards risk and accreditation and outlined the objectives of this workshop, which were to;

- Share the latest science findings from the Phyto-threats project

- Provide an interactive demonstration of science outcomes and tools

- Explore how the project’s science outcomes can best be used to support the continued development of accreditation and Plant Health policy

The meeting was attended by c45 stakeholders representing nursery managers, landscape architects and garden designers, Plant Health inspectors, foresters, academics, policymakers and others. This report provides an overview of the presentations given on the project team’s research, the Plant Healthy Assurance Scheme, key outcomes from the interactive science sessions and general discussions, and next steps to ensure impact.

Research Highlights

David Cooke (James Hutton Institute) presented the results to date from the project’s work package 1, which looked at the distribution, diversity and management of Phytophthora in UK plant nursery systems. He started by thanking the managers of partner nurseries who participated in the fine scale survey for permission to sample and ran through the objectives of this work. These were to manage the risk of import and spread of Phytophthora, generate data in support of biosecurity protocols, enable earlier detection of the next threat, and analyse the diversity of Phytophthora species in relation to nursery management systems. He showed a video of zoospore release to remind everyone that managing Phytophthora is all about managing water! He also reminded everyone of the life cycle factors which make Phytophthoras so damaging, the large diversity of known species, and then ran through the history of P. ramorum on larch as an example of why we want to stop the next Phytophthora!

David then presented the nursery sampling protocols for the fine scale surveys. This involved fifteen partner nurseries which were each sampled 4-5 times over the three-year project period, and the broad scale surveys which involved the sampling of a further 118 plant nurseries as part of statutory Plant Health inspections. The partner nurseries for the fine scale survey included a range of business types from forest tree nurseries to traders of amenity horticultural plants and garden centres. He reiterated that the sampling was not random, but targeted symptomatic plants and known Phytophthora hosts as well as management practices including water sources, drainage systems and run-off ponds. He then showed some photos illustrating the type of material sampled before running through the process of metabarcoding which identifies Phytophthora species based on their unique DNA signatures and the data analyses leading to reports of Phytophthora diversity in each sample.

The project collected 2869 root samples from 163 host genera, the top 25 of which were shown in a figure and included Juniperus, Taxus, Viburnum, Pinus and Rhododendron as the most frequently sampled species. The sample analysis is a two-stage process, with the first stage being a PCR test to determine whether Phytophthora is present in the sample or not. All Phytophthora-positive samples are then progressed to the second stage which involves Illumina sequencing to determine which Phytophthora species are present. Overall, 40-50% of all nursery samples collected were positive for Phytophthora. This varied according to host genus, with Chamaecyparis, Pinus and Fagus yielding some of the highest proportions of positive samples. In terms of Phytophthora test results in relation to nursery practices, the percentage of positive samples varied across partner nurseries from 20-70%, and this reflected the plant health status and nursery management practices observed at sampling. One key objective was to feed results back to the nursery manager to help them improve practice.

David then talked through species findings, with 51 Phytophthora species identified so far with P. gonapodyides, P. cinnamomi, P. cryptogea, P. syringae and P. lacustris as the five most common species. The clade 6 taxa (such as P. gonapodyides and P. lacustris) are generally considered native and less pathogenic and are abundant in rivers in Europe. However, the other abundant species (which, in addition to the above species, also included P. cactorum, P. cambivora, P. plurivora and P. nicotianae) are common pathogens on many hosts in the nursery industry. The important quarantine species P. ramorum has only been found in eight samples to date and P. kernoviae not found at all, whereas other regulated pathogens P. lateralis and P. austrocedri have been found in 17 and 10 samples, respectively, so far.

Some species of concern include P. cinnamomi, which is adapted to warmer environmental conditions, has an exceptionally wide host range and was found to be widespread on a range of hosts particularly in nurseries in southern England. Phytophthora quercina was found in the majority of Quercus plants sampled in the survey. This species is thought to be native to Europe and implicated in root damage and progressive decline of oaks. A DNA sequence matching (tropical) clade 5 species P. agathidicida/castaneae/cocois was found in many water samples, particularly in southern nurseries. David raised whether imported components of potting media (i.e. coir) could be implicated as the source?

David talked through some new species records for the UK and showed how outputs have been reported to nurseries with anonymised reports. He then talked about management practices affecting pathogen arrival (source and health of plant material coming in, growing media, water source, mud on vehicles/boots), pathogen spread on-site (including water management and hygiene) and pathogen dispersal off-site (quality control at sale, water run-off, plant disposal), i.e. how do we translate these findings into effective management practice? He then concluded his presentation with ongoing work/challenges, such as continued development of the detection tool, final PCR testing and sequencing of remaining samples and reporting to nursery managers, followed by meetings with nursery managers, Plant Health teams and those responsible for the development of the Plant Healthy Assurance Scheme to discuss the implications of the results and how they can be translated into improved practice and policy.

Discussion

Q: Did we see a relationship between the percentage of positive samples and type of plant or management?

A: Yes, either based on observed practices at sampling or nursery type, but generally there seemed to be a good relationship with practice. Data analyses will link Phytophthora species diversity to host and management practice to identify priority hosts and practices to target in an accreditation scheme.

Q: On the issue of plant disposal, would you recommend burning?

A: Yes, if it’s possible in your area, a pathologist would recommend this, but composting is an option too.

There followed some discussion on composting protocols, with some protocols already tested and shown to work.

David warned that a ‘hospital’ discard area should be treated as a contaminated zone – ideally don’t have discard piles and certainly don’t sell the plants as discounted or give them away (similarly with used pots).

Mike Dunn and Mariella Marzano (Forest Research) presented work package 2 studies on the feasibility of an accreditation scheme, giving perspectives from different stakeholders. Mike showed a few photos of good and poor nursery practice in terms of biosecurity and spoke briefly about best practice guidelines from an Australian nursery accreditation scheme. He then went on to describe the surveys conducted by the work package 2 team exploring perspectives on accreditation from different stakeholders including nurseries, retailers, landscaping sector, local authorities and the public.

Key findings from the consumer survey of 1500 plant buying members of the public found that they obtain plants from multiple sources (garden centres, DIY stores, supermarkets, friends and nurseries) so there is a need to consider the whole supply chain, not just nurseries, when developing accreditation. When making decisions about which plants to buy and where to buy from, factors such as quality, range of products offered, and cost are key drivers. When asked about which sources they feel are riskiest in terms of pests and diseases, it was clear that they are using sources they themselves would consider to be of higher risk (e.g. non specialists such as supermarkets and DIY stores). Thus, either education or promoting accredited products on the grounds of high-quality healthy plants is required. Existing purchases of non-horticultural products (fair trade coffee, red tractor produce etc) is driven by ideals and quality. The biggest interest in accreditation comes from the biggest spenders e.g. those who spend more are more likely to travel further for accredited plant products.

Moving on to discuss perspectives from nurseries, retailers (including garden centres), landscape architects and designers, based on 253 survey responses and 33 interviews, it was found that nurseries and garden centres have similar pest and disease concerns (e.g., Xylella and Phytophthora), but the largest proportion of landscape designers rated ash dieback as their greatest concern.

Mariella ran through some of the key comments and concerns from these sectors in terms of pests and diseases, with the reputation of the business, disruption, negative impact and the practices of other plant sellers being of concern, i.e. we might be doing things properly, but others aren’t, and the risk comes from there. Mike talked about perceptions of risk reduction by introducing a suite of biosecurity practices. Nurseries and garden centres reported an expected 25% (mean value) reduction in risks posed by Xylella and Phytophthora if they were to implement best practice, however around 55% of respondents perceived no reduction in risk though best practice. Although the best practices aimed at growers would be inapplicable to landscape architects and designers, 92% of these groups said that biosecurity and pest and disease issues influence their choice of plants when preparing planting specifications.

Landscape architects and designers may also include pest and disease precautions in the specifications. For example, they might outline that particular species should be used. This appears to be happening to some degree (around half of landscape architects and designers always/often include pest and disease precautions in their specifications). However, a limitation of the role of landscape architects and designers in the pest and disease conundrum is that there’s no guarantee that the trees and plants they specify will actually be planted in the way they intended or outlined. If an accreditation scheme became established in future, landscape architects and designers may advise that plants are obtained from an accredited grower.

Going on to look at the use of twelve biosecurity practices by nurseries, only four of the practices are currently used by the majority of nurseries. Having a quarantine/holding facility, water treatment and reliance on UK suppliers were all practices perceived to be most costly, whereas boot washing, disinfecting stations and vehicle washing stations were perceived to be least costly. Owing to a lack of clear guidance, nurseries varied in terms of how they approach biosecurity practices, such as disposal of waste/sick plants. In terms of driving good practice, retailers are influential consumers and could really help in driving good practice if they demand transparency in their supply chain, including biosecurity beyond the border.

In terms of attitudes towards an accreditation scheme, there was strong agreement from both nurseries and garden centres in; a) an accreditation scheme better ensuring the quality of trees/plants sold to consumers and b) safeguarding the wider environment from the spread of pests and diseases. So, clearly, there are some perceived benefits and agreement that accreditation would fulfil some very important aims. However, there was a mixed response in terms of interest from nurseries and garden centres in joining a hypothetical scheme. Both sectors were slightly more negative than positive, but the largest response category was in the middle (50/50 whether they would join a scheme). This might be because they were being asked to consider a hypothetical scheme with no detail on how it would work and what it would cost. During the afternoon’s interactive session Mike and Mariella ran an exercise to consider which factors stakeholders think are most important for an accreditation scheme to be successful.

Mike then ran over some of the challenges to accreditation such as reasons for non-adoption of the twelve best practice criteria used previously in the survey. So, after asking nurseries about what practices they did use, they then asked why they didn’t use the others. When offered a range of response options the most common reason was ‘inappropriate for size of business model’. The perception that ‘we don’t need those practices’ is perhaps the biggest barrier, even more so than cost! Again, the importance of these practices in pest and disease prevention may not be fully appreciated. There was some cynicism among nurseries and garden centres about insufficient interest among growers for accreditation to be successful, and the costs of such a scheme for growers and consumers. Mariella talked through some of the comments received from nurseries and garden centres in relation to their concerns over accreditation.

When asked about willingness to pay for the business and the stock to become accredited relative to their existing business costs (% premium), strikingly, the largest response category for nurseries and garden centres was 0%. However, if the costs can be kept low, say 1%, then 64% of nurseries and 60% of garden centres would be prepared to pay for accreditation.

For landscape architects and garden designers, their impact is limited because the schemes they specify for aren’t always carried out as they describe. Going forward, the option to specify that landscape contractors should attain plants from accredited buyers might be possible. However, real change could require those procuring contracts to put biosecurity concerns ahead of other factors (i.e., how timely or cheaply a site can be planted). If this were the case, demand for accredited products would increase, and interest in becoming accredited or stocking accredited tree/plant products would likely increase.

Mariella and Mike finished up by summarising their findings so far in terms of appetite for accreditation;

- Accreditation must cover multiple businesses, or at least their stock

- Many nurseries will have to improve their biosecurity practices to become accredited

- Few nurseries are willing/able to incur substantial cost to become accredited

- What accreditation ‘looks’ like (teeth, costs and benefits) will be influential

- More evidence is needed of how regulated pests and diseases could impact growers, and how biosecurity practices avert such risks

- Public are driven by quality rather than biosecurity practices. Thus, quality could be emphasised to promote an accreditation scheme

- A requirement for large landscape contracts to use stock from accredited growers would increase demand (and therefore suppliers’ interest).

- Retailers are willing to work with science and policy to improve practices and could serve as an important player in raising awareness of plant health

Discussion

Comments:

Online purchasing is a problem – how does that fit into accreditation?

Retailers don’t want negative messaging. Lots more discussion going on about biosecurity and raising awareness and providing peer pressure to change behaviour.

Need to establish the Plant Healthy assurance scheme.

Virtual nurseries – a huge problem.

Need to make accreditation compulsory.

Needs to be a requirement for accreditation with logo on the door of the nursery. Xylella is making a difference in a positive and negative way. There are nurseries in Italy who are in trouble and are keen to sell so are dropping prices and this puts pressure on some to buy cheap. Oak processionary moth is another huge problem – close to 60+ sites with it. Some nurseries were careful when importing oaks, but others shipped oaks without any paperwork.

Beth Purse (Centre for Ecology and Hydrology) presented on the results of work package 3 linking global spread and impact of Phytophthoras to biological traits, trade and travel, suitable habitat and climate. She described the process of pathogens as invaders, going through the stages of transport, introduction, establishment and spread, with the potential for invasion failure at each stage in the process. Beth’s team have been looking at which traits or biological characteristics enable a Phytophthora species to become successful invaders, overcoming all the barriers along the way.

Beth showed how Phytophthoras spread by trade and travel, presented a map of trade flows into Britain, and talked through how these pathogens are sensitive to climate and habitat conditions. The main aim of her team’s work has been to analyse pathogen behaviour and traits to identify and rank global Phytophthora threats to the UK. The specific questions they have been looking at are; i) how are Phytophthoras introduced into the UK?, ii) which species arrive?, iii) which species establish, and which parts of the UK are at risk?, iv) could tourism present a potential pathway of introduction?, and v) what range of hosts and sectors in the UK could be impacted?

In order to start looking at the above questions, Beth’s team developed a global Phytophthora distribution database from a range of sources, collating close to 40,000 country-level records covering a range of sectors from garden/amenity, forest, nursery and agriculture. They also developed a database of Phytophthora traits for all 179 described species, together with collaborators in Australia and New Zealand. Beth ran through the Phytophthora biological traits considered to be important at each stage of the invasion process. These include whether the species produce resilient resting structures such as oospores, chlamydospores and hyphal swellings, their thermal tolerances for growth, whether sporangia (sacs containing infective zoospores) are caducous (i.e. ‘deciduous’ allowing aerial dissemination) and whether they cause root disease or aerial disease, or both. They hope that the trait-based framework can be used as a predictive tool, so that when a new species is first described, key morphological or biological traits can be measured as a first priority to determine potential impact.

Looking at risks of introduction, Beth showed a map of annual live plant imports into the UK since 2000 in which it was clear that most live plant imports come from countries in the EU (e.g., The Netherlands and Ireland), but also that there is significant trade in live plants from the USA. Plants are also imported from Asia and Australasia – the global network is extensive. To determine what factors most influence risk of arrival of a new species into a new country, they looked at 35 Phytophthora species with more than one documented arrival in any country since 2000 and associated trait data, taking into account national recording and biosecurity effort in each country where these species have been reported. They found that introductions were strongly correlated with the level of connectivity to source regions by the live plant trade. They also found that some species are better able to exploit trade pathways than others, and that these tended to be cold-adapted Phytophthora species. Beth then showed the model that she will demonstrate in the afternoon session where, for any country, the user can look at import volumes of live plants from source countries and the Phytophthora species present in those countries. For recently discovered Phytophthora species (i.e. post 2014) the model also provides a link to trait-based predictions for future global spread of those species.

Moving on to risk of establishment, Beth’s team have collated a very large dataset of records of Phytophthora species detections in the UK from various sources. She presented a map of the UK showing locations where P. ramorum has been detected, as an example (including nurseries and the wider environment). They found that the more common Phytophthora species were recorded in nurseries as well as in forests and gardens. The thermal traits of species appear to have a strong effect on the latitudinal range of spread with cold-tolerance in Phytophthora linked to establishment at higher latitudes.

For the question ‘how much of the UK is at risk of a particular Phytophthora species establishing?’ Beth showed some global niche models using the already well-established invasive species P. cinnamomi and P. ramorum as ‘training models’. These models are still under development, but show very nicely the riskiest UK regions where each species has indeed established. Essentially, models with environmental factors and global occurrence data give accurate predictions of distribution in the UK wider environment. Different Phytophthora species vary according to which environmental drivers are important to their establishment in a region. For several species (P. cactorum, P. cinnamomi, P. cryptogea and P. plurivora), the seasonality of precipitation was the major driver. For P. ramorum, however, winter temperature appeared to be the most important factor.

Essentially, global niche models are a valid methodology for identifying suitable habitat for Phytophthoras in the UK. However, lots of occurrence data are needed to develop the models and this is not available for many species that are yet to arrive in the UK. Also, many

Phytophthoras are unknown to science when they first emerge in the invaded range. Centralised Phytophthora occurrence and trait databases integrated across sectors and enhanced sampling in Phytophthora source regions are needed to be able to develop models and predict species behaviour when invading temperate areas.

Beth then moved on to whether biological traits explain variation in global spread and host range of Phytophthora species. They looked at geographical extent (number of countries ‘occupied’ by that species) for 156 species, and number of different plant hosts recorded for 145 Phytophthora species. They found that cold tolerance, the ability to infect roots and the ability to cause foliar symptoms were the traits most associated with geographical extent. Wider host ranges were strongly linked to optimum growth rate, oospore wall thickness (i.e. long-term survival) and ability to cause both root and foliar symptoms. They then asked whether thermal traits, especially cold tolerance, modulates invasion of Phytophthora into temperate regions. There are certainly indications that cold-tolerance may be more labile than heat tolerance which could have implications for colonising new regions, particularly those at higher latitudes. Looking across the Phytophthora phylogeny (classification) thermal traits and cold tolerance, which Beth’s team have linked to invasion success, are very variable suggesting recent adaptation.

Summing up findings and horizon scanning; connectivity to source countries through the live plant trade is strongly linked to introduction, and species that are cold-adapted are better able to exploit the live plant trade pathways. In terms of risk of establishment in the UK, cold-adapted species establish further north in the wider environment. This is predictable from global niche models, and the global climate limits of each Phytophthora species are linked to their biological traits. In terms of impact, phylogenetic relatedness is as strong a predictor of global impact as biological traits. Years known to science is also important as biological and distribution information is gathered on each species over time. Cold tolerance and ability to cause root and foliar disease predict geographic extent. Thick oospore walls, faster optimum growth rates and ability to infect both roots and foliage lead to wider host ranges. Closely related species are similar in impact. Phylogeny + traits explain 50-60% of the variation seen in host range and geographical extent for Phytophthora species, so these factors could be used in horizon scanning when looking to predict the potential impact of newly discovered species. However, the traits looked at in this study were those traits measured routinely for species descriptions – are we missing other key traits linked to invasion?

Beth concluded her presentation by stressing the importance of the global Phytophthora databases developed as part of this study being available to researchers and other end-users, being updated as new species are described and information becomes available. She also showed how her team’s model outputs can help influence policy and practice, for example the Phytophthora importation tool, models for predicting species’ likely impact in the UK, and another tool listing Phytophthora hosts in UK forests and commercial forestry, which could be used to inform species choices for commercial planting and afforestation. Beth asked the audience whether they would be interested in using any of these tools to inform their practices, and if yes, whether their practices could change as a result of the tools. She also asked what modifications or additional information would they like to see in the tools or models to improve usefulness, and how best to access the tools, i.e. website, phone app? It was hoped that useful discussion on these questions could be had during the afternoon’s interactive demonstration of the tools.

Discussion

Q: Do you have any Phytophthora data from Ireland?

A: Yes, we have data from both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Q: Cold-tolerance (temperature) is mentioned a lot in establishment, but what about precipitation?

A: Yes, rainfall is key e.g. evidence for autumnal moisture having an impact on P. ramorum/ P. kernoviae, but also survival during dry conditions is important.

Ewan Mollison (University of Edinburgh) gave a brief overview of the work package 4 research on predicting risk via analysis of Phytophthora genome evolution. Phytophthoras are oomycete pathogens that cause serious plant diseases and there are around 170 species currently described. More species are being discovered all the time, mainly as a result of global surveys looking in source regions of suspected high Phytophthora diversity. We know that the impact of Phytophthora varies among species and that when a new species is discovered it is very hard currently to predict its impact. One of the bases for this study was to see whether impact can be predicted by the genes that a species has through a study of Phytophthora genomics.

After an explanation of what is meant by ‘genomics’ (determining the entire DNA sequence of organisms and fine-scale genetic mapping), Ewan ran through the rationale of the work, which was to sequence the genomes of three Phytophthora species currently regarded as less-damaging, but which are closely related to highly damaging species. By comparing the genes present in less damaging species with those of highly damaging species, it might be possible to find genes present in damaging species, but absent in less damaging species that might be linked to virulence. Ultimately, gene content might help us to predict which newly discovered species are likely to have most impact.

So, the project team set about sequencing the genomes of i) P. europaea which was first described from soil associated with European oaks, but which is closely related to P. alni, a hybrid species killing riparian alder across Europe, ii) P. foliorum, currently known only to cause a minor foliage blight of azalea and rhododendron, but which is closely related to P. ramorum which is killing larch in the UK and tanoak in the USA, and iii) P. obscura, first associated with horse chestnut and pieris, but closely related to P. austrocedri, which is killing juniper in the UK and Chilean cedar in Argentina.

Ewan ran through the process of genome sequencing, which is to extract the total DNA from each organism, fragment the genome, apply a new sequencing technology to generate millions of sequence reads from the short DNA fragments, then use computer software tools to assemble the overlapping DNA sequence reads to produce a complete genome. In order to be able to look at the gene content of a genome with any accuracy, it is very important to have as complete a genome assembly as possible, i.e. to have the final genome construction in as few fragments (known as ‘scaffolds’) as possible. Using the latest sequencing and assembly technology, Ewan and the team were able to produce three of the most complete Phytophthora genomes yet produced for a Phytophthora species (at this time 30 Phytophthora species have had their genomes sequenced) i.e. the P. foliorum genome assembly has ~ 60 million DNA base pairs assembled into just 22 fragments.

Each of the three genomes sequenced in this project have ~19,500 predicted genes and Ewan presented two slides with figures showing a comparison of the genes present in each of these three less-damaging species with the genes present in closely related highly damaging Phytophthora species. The figures showed how many genes are shared and how many are unique to each group of species. Initial analyses revealed 40 genes present in highly damaging species which are not present in the less damaging species and which might be linked to virulence. The next steps are to analyse the function of these genes in order to start to unravel what makes a Phytophthora virulent. Gene content can then be used to predict which newly discovered Phytophthora species have the potential to be most damaging.

Update on the Plant Healthy Assurance Scheme

Helen Bentley-Fox and Amanda Calvert (Grown In Britain) presented an update on the Plant Healthy Assurance Scheme. Helen is the technical manager for the Grown In Britain standards, and Amanda is an auditor with nursery expertise. For the last one and a half years they have been working with the HTA and Alistair Yeomans to develop the Plant Health Management Standard which will form the basis of the Plant Healthy Assurance Scheme.

Essentially, the Plant Health Management Standard is a checklist for anyone who works with plants to deliver plant health. It is based on the International Plant Protection Convention’s framework for pest risk analysis. The idea is for plant producers to use this checklist and be subject to periodic reviews to help them improve their plant health management. The Plant Health Alliance Steering Group is the governing body for the Plant Health Assurance Scheme which provides the overarching implementation of the Plant Health Management Standard. Growers can sign up to the scheme, be audited against the standard and publicise that they are part of the scheme through use of the Plant Healthy logo. The scheme details how companies are audited, by whom, how often and how. The intention is that Plant Healthy unites all other grower accreditation schemes into a single all-encompassing scheme. Although the scheme has not yet been rolled out, an online Plant Healthy self-assessment tool is available and allows businesses to identify where they could improve their biosecurity before joining the scheme. Around 200 people have completed the online self-assessment to date.

The Plant Health Management Standard has a list of 23 requirements that demonstrate that a business is operating responsibly. These 23 requirements are designed to improve the health of the plants that are bought and sold, and to enhance biosecurity. The tricky bit with the standard was to not be over-prescriptive. They aimed for something generic enough to cover all businesses, but specific enough to be auditable and effective. The Standard is available on the Plant Healthy website https://planthealthy.org.uk/resource-topics/sector-guidance-documents with guidance documents provided for all the different sectors right down the plant supply chain from propagators to landscapers. These documents explain how each sector can apply the Standard to their businesses.

The Plant Health Management Standard was developed under two key concepts; i) Appropriate Level of Protection (ALOP; World Trade Organisation) and ii) Pest Risk Analysis (PRA; International Plant Protection Convention). These are normally reserved for nations, but have been applied here to a ‘site’ or business to enable a joined-up approach to plant health biosecurity. Amanda and Helen presented a slide showing the pest risk analyses procedure for each business as a cycle; essentially the boundaries of the ‘site’ (business) are identified, the plant species handled within that site identified, any potential pests and diseases affecting those plant species identified, the pathways of introduction of each pest and disease mapped, and the level of risk to that business if controls are not in place identified. The control measures are then identified and the degree to which each measure can mitigate the risk. The Appropriate Level of Protection is defined for that site and monitoring put in place to demonstrate the effectiveness of controls and management systems. It was emphasised that this is a continual process and not static. Underpinning the cycle of risk assessment is training of staff and recognition of risk.

The latest update on the scheme is that the Plant Health Biosecurity Alliance are meeting this month to approve the business plan, secure funding and the certification process. The scheme will be launched to all trade sectors in spring 2020 with a ‘soft’ launch to the public later in the summer. They need to train more auditors however and the Plant Healthy logo can only be used for the company, not on each plant, as the plants might move on to a business not applying the standard.

Amanda then ran through the audit process, which are covered in the following steps;

- An online form is filled out by the company to enable the auditor to plan the audit and the process, i.e. which members of staff do they want to see etc?

- The auditor arrives on site and makes observations of the surrounding environment.

- Paperwork and site assessment: staff are interviewed, information gathered on location, size, no. of employees etc. The director must be present as they are the lead and their influence is disseminated down.

- The legal requirements are then assessed; plant passports, phytosanitary certification, forest reproductive material regulations. Evidence and records are looked at followed by on the ground spot-checks.

- The business plant health policy is examined, this policy is not their detailed written records of protocols, but the higher level aims. Each site needs a statement scoped according to their business.

- Plant health responsibilities must be assigned to staff with a flow chart of people involved. Staff are interviewed to determine how information flows along the chain.

- The business plant health risk is identified, and an assessment done to ensure that the specific plans and protocols are in place to reduce these risks to an Appropriate Level of Protection – are the controls fit for purpose?

- Supply chain management; businesses must show evidence of having risk-assessed their suppliers.

- Plant health hygiene and housekeeping measures are assessed, such as the growing media and soil, water and weed management, cleaning (i.e. dirty pallets), waste treatment and disposal, site water drainage and run-off, vehicle cleaning – they ask, for example, ‘where you were last?’

- Plant health controls are checked to ensure good records and data, including all plant labels and codes. Plants coming in – where do they go to after they arrive at the site and are they checked for health? Same for plant dispatch. How are complaints managed?

- Requirement for ongoing self-assessment of plant health and for continual staff training and recognition of plant health competencies.

Discussion

Q: What if someone fails the audit?

A: They do not get the logo, but if they are close to passing then a progress plan is needed. They are given feedback and are graded so they know which areas need more work and these, especially, will be checked for progress the next year. Auditors are trained so that they all apply the same level of evaluation to each business.

Q: How does this link with other accreditation schemes?

A: The aim is for a single, overarching accreditation scheme, which is Plant Healthy.

Comment: It is hoped that the outcomes from the Phyto-threats project will feed in, and inform, this scheme.

Comment: Yes, we have a standard, but the way it is written means that novel information will enable the company to take this information on board to continually upgrade their processes.

Q: This is for nurseries. What about a garden centre? If plants from an accredited producer sat next to a sick plant from somewhere else?

A: Yes, we plan to extend the scheme to retailers to make sure the system goes right down the supply chain.

Q: How will arboriculturalists benefit? How will you get them on board?

A: The standard can be applied to arboriculturalists. Both the Landscape Institute, British Association of Landscape Industries and the Arboricultural Association have their own best practice guidance and the scheme references these.

Q: How prescriptive do you plan to be for water testing? For example, if filters need to be cleaned, do you insist a test is the best idea for a filter and insist on it being done?

A: More prescriptive conditions may come as scheme develops, but it’s not currently prescriptive. We highlight a problem area and say that it is a problem and ask how they will tackle the problem, this is an example of not being overly prescriptive – how they tackle it must suit their business and they can choose any number of ways. We would make a point of checking during the next audit. The idea also is that it will encourage businesses to improve; for example, training, if they need to update knowledge in certain areas.

Comment: The Phyto-threats project will identify a set of priority management practices for the standard, likely based around water source and usage, growing media, raising plants off the ground. These could be referenced in scheme guidance.

Interactive demonstration of project tools and outcomes

Best practice and water treatment options

David Cooke presented on nursery best practice in relation to Phytophthora findings at nurseries so far and Tim Pettitt (University of Worcester) presented different water treatment options; the pros and cons.

Outcomes: there was much discussion on what to do with the waste plants and growing media. It’s a big challenge and the options are burial, burning, composting. Drying and incineration was suggested as an option, also pelleting and burning-green energy.

Q. Is it OK to use rainwater collected into a tank? (asked twice)

A. Rainwater can become and often is contaminated with oomycete plant pathogens, surprisingly small amounts of infected debris on roofs or more likely in gutters can cause problems – often contaminated rainwater will have a wonderfully clear appearance. On the ‘up’ side, rainwater is very good quality generally and easy to treat to remove plant pathogens with any of the available technologies which all work well on this water source.

Q. On UV effectiveness with increasing turbidity of water.

A. You can pre-filter, but even cleared water may have UV-dense materials, such as dissolved organic materials that reduce the transmittance and render the treatment less effective. Also, even tiny particles (<25 µm) can scatter UV light and cause problems with treatment efficacy.

Q. How can you be sure that wetland species don’t propagate Phytophthora?

A. We can’t! However, monitoring of two commercial irrigation water treatment systems treating water with floating flag iris has consistently shown removal of Phytophthora and Pythium spp. (although not related oomycete species Saprolegnia ferax). Also, similar systems have been apparently used successfully in Zundert in the Netherlands since the early noughties. The mechanism for these ‘removals’ or population declines is not properly understood and the possibility of the iris roots in such systems becoming infected by pathogenic Phytophthora or Pythium species with wide host ranges has not been properly explored. (more information is available in AHDB review CP126, see pp 90-92)

Q. What’s the environmental footprint of waste treatment? (costs vs carbon footprint)

A. I don’t think this has yet been effectively studied in-depth. All water treatment systems will have capital costs for equipment and storage, and these vary between treatment systems, with some having lower installation costs (e.g. in-line dosing systems). Running costs will involve power for systems such as UV and ozonation and especially pasteurisation as well as increased amounts of pumping to move water through systems and to/from storage, whilst dosing systems have the recurrent cost of the chemicals used. Full assessments of carbon footprints can only really be properly achieved on a case by case basis and I don’t think this information is yet available.

Q. How often should you change MyPex matting?

A. It depends what the MyPex is sitting on and its general condition. Obviously, if it becomes damaged or heavily contaminated with mud and debris it should be replaced. However, if it is on top of a reasonably well drained gravel or sand bed, and so long as debris and weeds such as moss and liverworts are removed, then it should be possible to use sterilants like Jet 5 or similar to clean the matting and remove pathogens between crops and matting should only need replacing when it becomes physically damaged. It’s impressive how big an impact simply washing and sweeping debris off the surface of matting can have in terms of reducing pathogen inoculum, although this alone is no panacea!

Feasibility of accreditation

Mike and Mariella ran an exercise to consider which factors stakeholders think are most important for an accreditation scheme to be successful in terms of uptake and impact. Participants were presented with a list of 9 factors which may influence success, as determined through surveys and interviews with actors from across the horticultural supply chain. These factors included:

Each person was asked to rate the following options in order of importance:

- Right biosecurity practices i.e. those with a demonstrable impact on reducing the introduction and spread of pests and diseases

- Greater public awareness

- Greater industry awareness

- Buy-in from those contracting planting schemes (local authorities, conservation bodies etc.)

- Low-cost membership

- Carrots for participants e.g. assurance that they won’t be punished for the presence of pests and diseases when seeking to improve biosecurity

- Sticks for participants e.g. penalties for failing to meet a scheme’s biosecurity standards

- Scheme branding – emphasising healthy plants (quality) and safeguarding the wider environment as well as the use of a recognisable logo

- Involvement of industry in scheme’s establishment and evolution

Participants were invited to reflect on and discuss these factors in order to clarify what each encompassed. Participants were then encouraged to suggest other additional factors which may determine a scheme’s success. Once a shared understanding of the factors was reached, participants were tasked with a voting exercise designed to elicit the relative importance of the factors. Specifically, each participant allocated a finite number of points (using 10 stickers) across the list of factors, with more points reflecting greater importance. In all, 37 people participated in the exercise including representatives of landscape architects, garden designers, government, Plant Health inspectors, environmental charities, nurseries, botanic gardens, conservation volunteers, the RHS, arboriculture consultants, commercial foresters and research.

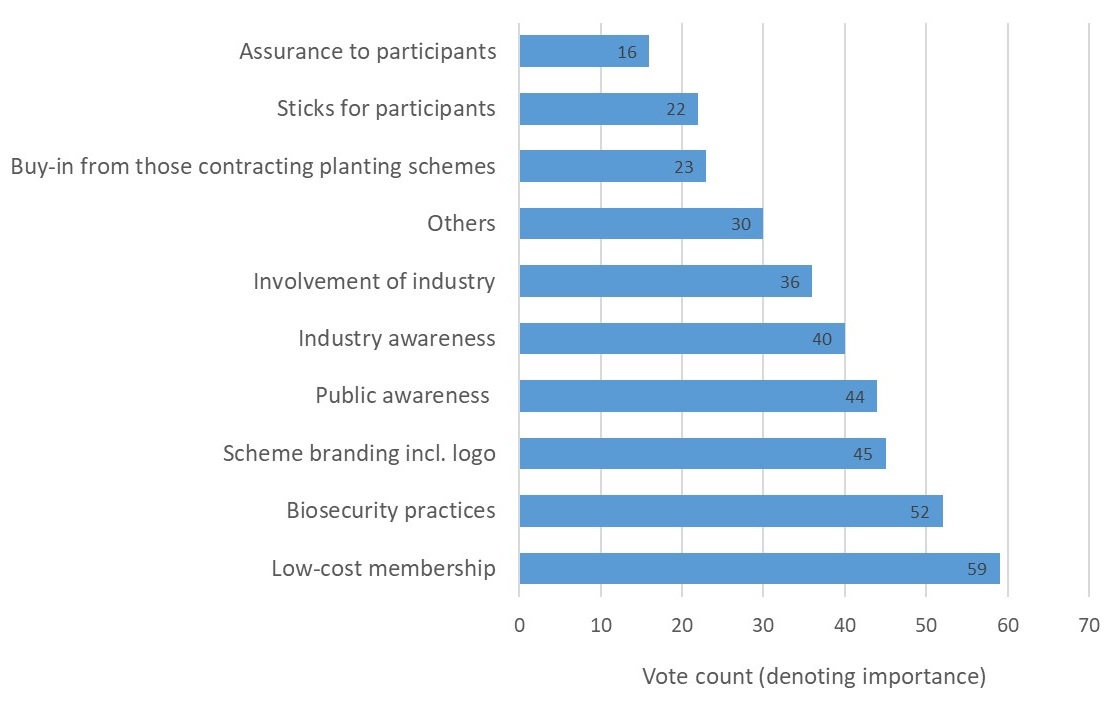

The outcome, presented in Figure 1 below, revealed that low-cost membership was considered the most important factor to ensure an accreditation scheme’s success. The ‘right’ biosecurity practices emerged as the second most important factor, followed by a number of factors relating to increased awareness of pest and disease impacts, biosecurity practices and the scheme itself. The most commonly suggested ‘other’ factor which could determine a scheme’s success was ‘mandatory involvement’.

Figure 1: Factors for accreditation success as ranked for importance by 37 stakeholders.

Demonstration of modelling tools to predict risk

Beth and Louise demonstrated a collection of online tools in development, which would allow users to interact with the data and modelling outputs from the Phyto-threats project.

Stakeholders were asked

- Would you use any of these tools to inform your practices?

- If yes, how could your practices change as a result of using these tools?

- What modifications or additional information would you like to see in the tools or models to improve their usefulness?

- In which format would you like such tools to be delivered? e.g. website, phone app.

The session explored three tools with stakeholders:

- Where are Phytophthoras coming from?

This tool focusses on the role of international trade in the movement of Phytophthoras and allows users to visualise the Phytophthora diversity in exporting countries and the volume of imports from those locations. Stakeholders were asked whether this would be a useful way to assess the risks of importing plants from different origins.

Q: Could the tools include information about Phytophthora and seed imports?

A: This will depend on whether trade data identify seeds within the commodity types – Beth and Louise will check if this information is available in their trade data.

The trade data in the tool sparked a useful discussion about the lack of information about traceability:

Comment: It is useful to know specific countries that are potential sources of Phytophthora, but the trade flow data do not capture the complexity of plant supply chains, which can involve multiple steps between countries. The poor traceability of plants prior to the previous country in the supply chain was highlighted as a problem for nurseries when buying plants.

Comment: Plant passports from Defra can tell us an origin, but plant only needs to be in UK for six weeks to become British.

Comment: APHA are making efforts to trace back origin of outbreaks for particular tree hosts.

Comment: Phytophthora source data could be useful when sourcing plant material from further south in Europe, in the context of climate-proofing.

Comment: One envisaged application was to look at threats from fungicide resistance in the pathogens in the country of origin. If importers knew this, they could think about not importing plants from some countries if it’s too risky (e.g. China fumigate all plants from Europe and pressure wash, so there are opportunities to tighten up biosecurity).

2. Which Phytophthora are associated with hosts in UK forest and forestry?

This tool is an interactive database of Phytophthora pathogens and associated hosts, which is searchable by host and by pathogen and links to risk maps of UK suitability for the pathogens.

Q: Could the tools be rolled out to cover a broader range of pests and pathogens?

A: The data for a number of other pests and pathogens of concern like Emerald ash-borer and Xylella are available from the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, where Beth and Louise are based.

3. Prevalence of Phytophthora species in UK nurseries and the wider environment.

This tool allows users to interact with maps of Phytophthora disease records in the UK. The maps show which species are predominantly nursery-associated and which are common in the wider environment. Host information is available by hovering over the record on the map.

Q: Will the tools be password protected, or will nursery locations be protected when displaying Phytophthora records? In many regions, nurseries could be identified even if the data were shown at 10 km resolution or even county.

A: Only Phytophthora reports from the wider environment (not nurseries) will be displayed when the tools are made publicly available.

General questions and comments from stakeholders:

Q: What is the added value of these tools beyond what is already in, for example the UK plant health risk register and plant portal, the EPPO alert list or the Plant Healthy portal?

A: The tools should provide more information about the relative risk of these species.

Comment: The Risk Register now has thousands of pests and diseases which makes it difficult to know what to zero in on.

Comment: Beth and Louise need to think about how it can be made relevant and linked in with industry? It would be of value to run a series of workshops to draw in key users and trial the tools.

Q: Could the tools be made simpler for risk assessment?

A: Model outputs could be translated into estimates of relative risk (e.g. ranking species or countries).

Comment: Visual nature of tool is very helpful. Perhaps it could be used to raise public awareness of threats from Phytophthoras and motivate the public to ask nurseries about what they are doing about pathogens.

Key outcomes

There was general agreement that a website would be the most useful format to access the tool. Potential uses of the tools were identified including identifying high risk Phytophthora species, hosts and source countries for users at different stages within the plant supply chain, to prioritise plant health surveillance and as an educational tool for the public. Improvements were also highlighted including simpler and more interpretable metrics of risk, broader coverage of pests and pathogens (a one-stop-shop) and the resilience and substrates used by different Phytophthora species. There was an appetite among stakeholders for further co-development of the modelling tools.

Role of genomics in predicting risk

There was considerable discussion around how genomics tools can assist future management. One of the ways to assist international plant health protocols is to be able to undertake a quick genetic test to determine whether a newly discovered species is likely to be highly virulent. We are a long way from that at the moment, but our work aims to take us there, if possible. For example, Phytophthoras have genes known as RXLR effectors which are linked to virulence. Some of these effectors may be more key than others in determining virulence. The number of these effectors varies greatly among species, e.g. about 350 each in P. sojae and P. ramorum and over 550 in P. infestans. These effectors tend to be associated with rapidly-evolving regions of the genome and may even play a role in how Phytophthoras can adapt to host resistance.

There was discussion on host jumps;

Q: P. ramorum jumped host, so how related to larch were its previous hosts?

A: Not related at all! Larch is the first known conifer host for this pathogen.

Q: What makes a species jump host, genetically? i.e. can a genome study help us to identify the potential for a species of Phytophthora to jump to a new host?

A: We don’t know this at the moment, but that is something that might become apparent as genomics advances.

Q: Is there potential for a species of Phytophthora to wipe out an entire host species?

A: Hopefully not if there is genetic diversity in the host population, where some individuals will have genetic tolerance to the pathogen. Larch is a commercial forestry species which is probably not very genetically diverse and is often grown in single species blocks, allowing rapid spread of the pathogen through the susceptible crop. With P. austrocedri on juniper, which is genetically diverse, we think we are seeing resistant individuals which do not develop disease. Hopefully their offspring will carry this resistance to allow a certain amount of population recovery.

A: We don’t know this at the moment, but that is something that might become apparent as genomics advances.

Q: Which clades of Phytophthora are most damaging?

A: There’s no real correlation between clade and damage – more a case of clades tending to be less damaging within their own “native” environment: e.g. David Cooke’s comments about clade 6 species being less of a problem in the UK.

Q: How much does copy number variation influence pathogenicity of Phytophthora?

A: Some evidence that elevated copy numbers or higher ploidy can lead to a more aggressive Phytophthora (e.g. in P. infestans).

Q: Are genomic methods used for other pathogen types?

A: Yes – widely used with other pathogens, e.g. RNA-Seq experiments to examine changes in host gene expression during infection; and genome sequencing of fungal, bacterial and viral pathogens.

Q: Has any work been done using knock-outs or knock-down experiments to investigate gene function in Phytophthora?

A: Not that I know of, but would be an excellent way to verify experimentally genes involved in pathogenicity.

Q: What about using GM to control Phytophthora?

A: Might be an option with regard to developing resistant plants (but runs into a minefield of laws and regulations!).

Q: Can we work out the age of Phytophthora species?

A: With phylogenetic analysis of multiple gene sequences we can track changes backwards to estimate at which points different species diverged.

Q: Are there similar genomic studies being used to predict potential hosts/resistant plant species?

A: There is a great deal of research into identifying / selecting resistant plant species / cultivars, but not so much (as far as I know) into identifying what makes a species more susceptible.

Q: Is there a risk of biocide resistance arising in Phytophthora?

A: Definitely – as with biocide resistance in any pathogen, there will always be some cells that are less susceptible than others and excessive or inappropriate use of biocides risks creating an environment where these have a competitive advantage.

General discussion

The workshop concluded with a short general discussion session with the following questions, answers and comments from the stakeholders and project team;

Q: Should accreditation be mandatory?

A: It makes it viable.

Comments:

A mandatory accreditation scheme means costs and who pays?

Science projects are good, but strong links are needed to be sure accreditation is science based.

Demonstration of best practice on nurseries might help to get buy-in from nurseries?

How to engage with the ‘hard to engage’, for example contractors?

Next steps

The project science team will continue to liaise with the Plant Healthy Assurance Scheme in terms of helping to develop the Plant Health Standard and in securing uptake and consumer support. We will also liaise with policymakers and practitioners over predictive models to ensure that our project outcomes are used to support pest risk analyses and the risk register.

Phyto-threats project team meeting November 2019

November 14th 2019 held at APHA, Sand Hutton, York

The aim of this meeting was to bring the entire project team together to share and discuss research progress since the last all-project team meeting on November 20th 2018, to outline planned outputs and to discuss next steps for continuing collaborations now that the project is finishing.

The science updates for each work package were presented the day before at the stakeholder workshop and a full report on each work package is available in the stakeholder meeting report published online:

Therefore, the report here focuses on additional information not presented at the stakeholder meeting and on the resulting discussion.

WP1 Phytophthora distribution, diversity and management in UK nursery systems – David Cooke (JHI) and Peter Cock (JHI)

David Cooke started off by emphasising the need to get back to the different organisations with an interest in the outcomes of this work package and to think about how best to engage. He planned to show today the Phytophthora species findings by nursery and for Peter Cock to show progress on the bioinformatics pipeline. They also need to link Phytophthora findings to nursery management structure with Beth’s team.

While David was running through the slides a question was asked regarding clades;

Q: Are you going to give a breakdown of clade when reporting back to nursery managers?

A: We had decided not to report clade, especially as sometimes clades change.

Comment: Nursery managers don’t need to know clade.

Q: But, isn’t there a clade-specific treatment or approach? i.e. clade 6 species tend to be less damaging than clade 8 species.

A: Grouping by clade might be risky, for example sending out a message that all clade 6 species are ubiquitous in water courses and not problematic. What about P. pinifolia for example? That one is a damaging needle pathogen of radiata pine in Chile.

Comment: We have this unknown clade 5 sequence cropping up in water samples at several nurseries. Clade 5 are regarded as tropical species, so this is most likely to represent a tropical Phytophthora and we think about it differently. Basically, if it affects how a species is dealt with then we should report clade.

Comment: Should we then include information on traits for each species found? i.e. provide a link in each nursery manager’s report to the traits’ database online. This means we put a simplified version of the traits’ database on to the Phyto-threats website and in our report to nursery managers we say ‘For more information on each species found and clade, follow this link…..’ It would have to be digestible for general use so should say e.g. oospores, chlamydospores, soilborne, airborne, damaging to which host etc.

Comment: Clade 11 has to be included somehow.

FR are currently pulling together distribution maps based on UK findings of Phytophthora species and it was suggested that these maps also link in to the Phytophthora traits’ database when that goes online. This would be useful as it would allow nursery managers to see the distribution of those species in the UK.

Comment: The species distribution maps should differentiate records from cultures vs DNA findings. There is a danger of reporting a species based on DNA findings only when Statutory Plant Health policy is currently based on the need for a viable culture.

Comment: We need to look at technology and how it relates to policy – does Plant Health policy need to catch up with technology and start to base actions on DNA findings too?

Comment: The sequences of all the species will go on GenBank; a few species can’t be differentiated using ITS1.

Q: Ultimately, could you offer this metabarcoding technology as a service for the public good? i.e. as a testing service?

A: That could be possible. This metabarcoding method would really lend itself to being developed and used as part of statutory plant health surveillance of nurseries. There are already some commercial companies specialising in eDNA barcoding, so this could be an extension of the services they offer. Water in nurseries could be tested, and then re-tested every few years. This might be a tool to assist in the issue of phytosanitary certificates.

Moving on with the presentation, David showed a slide listing host genus sampled by survey type, i.e. fine scale and broad scale, to illustrate the different range of hosts sampled. In the broad scale survey, the hosts were largely ornamentals with viburnum the most commonly sampled host, followed by rhododendron, camellia and pieris. David then showed the percentage of Phytophthora-positive samples for the broad scale and fine scale surveys – all around 40-50% positive.

Q: Can we relate broad scale survey results to practice?

A: We only asked for 5-10 samples per broad scale nursery – with each sample taken from different batches of plants. On average we received 6.3 samples per broad scale nursery which is possibly too few to link to practice. Also, associated metadata were not collected for the broad scale survey, only host symptoms description. However, APHA and SASA have knowledge of the background of each nursery, for example import history might be useful – a plant may have arrived with a Phytophthora and not acquired it in that nursery. We have scanned copies of each broad scale sampling sheet and those can be referred to when interpreting results.

Back to the presentation, David showed that over 70% of DNA sequence reads produced so far have matches to known Phytophthora species on the database. However, 7% of reads match unclassified Phytophthora species. So, it appears that there are quite a few unknown species in the samples.

Q: What about the ypt gene which has been used as an alternative barcode for Phytophthora?

A: There have been some issues with the ypt gene mainly due to it being only single copy. We are planning to look at other barcoding options as a separate project.

David then went on to show Phytophthora species diversity by nursery and this generated much discussion on how management practice affects diversity. There were clear examples of how certain species predominate at certain nurseries, with nursery size, practice (in particular importation of stock) and geographical location appearing to have an effect on species diversity. E.g. P. cryptogea (broad host range) was top, followed by P. gonapodyides, P. cinnamomi and P. plurivora. Records of P. pseudocryptogea and P. cryptogea are put together. One nursery has lots of P. cryptogea. Another has almost no Phytophthoras and operates with very tight biosecurity.

Comment: The Phytophthora species that we find on trees as part of our FR advisory service do seem to match species found in nurseries. For example, P. plurivora is our most common species on trees and P. cryptogea/pseudocryptogea is very common in agricultural soils and we find it causing serious root rot of trees planted on former agricultural land. We should try to match nursery findings to FR’s Tree Health Diagnostic Advisory Service findings in trees.

David moved on to discuss ongoing work/challenges, which, in addition to the need to complete sample processing, report to nursery managers and liaise with Plant Healthy Assurance Scheme over results, included continued refinement of the detection tool – the very high sensitivity of metabarcoding is both a blessing and a curse! For example, the need to prevent and account for field and lab contamination through the use of synthetic control sequences. Also, the computational pipeline development, coping with reads beyond 1-2bp thresholds, species boundaries and visualising data outputs.

David concluded his presentation with final thoughts/conclusions; metabarcoding is a very powerful, targeted method for exploring microbial diversity. A classifier has been developed, although results are interpreted with caution. When confident, the data will go to GenBank. With expanded primer sets we could look at other oomycetes. The sample bank of eDNA offers huge potential and experiments are now needed to advance biology and ecology.

Peter Cock presented on the bioinformatics pipeline THAPBI-PICT now published online https://pypi.org/project/thapbi-pict/. He talked about technical variation in metabarcoding, determined through the use of four synthetic DNA control sequences alongside real samples. Illumina produces 1000s of sequence variants generated in very low abundance. These 1bp variants are most likely PCR artefact as single base change by PCR can happen and we need to account for that in metabarcoding diagnostics. Lots of these variants are coming through at low level. These variants were used to set a minimum threshold, which was 100. This means that any unique sequence needs to be present at least 100 times before going through the pipeline; i.e. any unique sequence at abundance of less than 100 is dumped early on in the pipeline. Sequence thresholds are then set for each plate for reporting species in a sample based on the level of contamination of synthetic control sequences in environmental samples. So, this is a plate-by-plate threshold set above the highest level of known sequence contamination.

Peter ran through how sequence data are prepared, by quality trimming FASTQ reads, merging the overlapping FASTQ reads into single sequences, discarding reads without both primers, converting reads into a non-redundant FASTA file and then filtering reads with hidden Markov models of ITS1 and synthetic control sequences so that non-matching sequences are discarded. This results in big data reduction!

Peter then showed edit graphs to illustrate the number of ITS1 variants observed for each species. Many at low sample abundance are likely to be PCR variants, but those occurring at higher sample abundance and with higher read numbers could be true ITS1 variants within the genomes, for example in P. austrocedri and P. nicotianae. There are also lots of Peronosporas and Phytopythium. Complex ITS1 clusters with up to 3 bp edits are observed for P. rubi and P. cambivora (the latter which is likely to be a hybrid complex?), but the most complex cluster occurs with P. gonapodyides, P. megasperma, P. chlamydospora, P. lacustris. All of these species are hard to distinguish by ITS1. So, the cut-off very much depends upon the species, sometimes 3bp difference works, for others we have to use just one bp difference.

In terms of interpreting sequence space, there seem to be some novel species in our sequence data. Species classification starts with a 100% match to a database sequence. If there is no perfect match, then the classifier looks for a 1bp difference. The database has ~170 individual sequences curated to species (by David) plus a much larger set of sequences from the NCBI database. Any sequences not matching the curated database, but which match the NCBI database based on 2bp difference, are reported to genus only. If it doesn’t match anything then it is marked as ‘unknown’. The pipeline does not use Swarm any more as it is too ‘fuzzy’. Looking at complex sequence clusters, these could be curated manually if we want to know what the non-matching species or genera are.

Comment: Sometimes we only manage short reads for an organism so it can’t be identified, but we have isolated it and we can see it’s a Phytophthora. The point is that we can still miss things using metabarcoding methodology.

Peter showed the outputs produced by the software tool THAPBI-PICT, for example the Excel spreadsheet of results. He has tested the classifier on other Phytophthora datasets as well as a nematode ITS1 dataset and found that it works well. The team plans to publish a paper on the THAPBI-PICT software, another on the use of synthetic controls, the nursery sampling dataset and an environmental monitoring paper. They hope to try and culture some of the novel Phytophthora species that the data hints at.

There was some discussion of the method and also on the Phytophthora community analyses planned for the nursery data. It was decided that there are enough data now to start planning these analyses, i.e. categorising factors to include in the analyses. This needs to link in with the nursery surveys that Mike and Mariella did, i.e. to categorise nurseries based on management practice/behaviour. Mariella has lots of information on partner nursery type and practice and if Beth gave her a list of what classification criteria they want, Mariella will pull it out and pass it on. The challenge with management factors is that some are easy to categorise, but others are qualitative and hard to rate, for example level of biosecurity practice. David is to give Mike a framework of what he needs, and they will provide it. Beth said she was planning to provide details on the information she needs after Xmas.

WP2 Feasibility analyses and development of ‘best practice’ criteria – Mariella Marzano (FR) and Gregory Valatin (FR)

Gregory Valatin presented on the costs and benefits of implementing nursery best practice from a nursery perspective, based on data pooled from 75 nurseries. The data come from three sources; an initial FR survey of nine nurseries, joint visits by FR and Fera to eleven nurseries and the work package 2 nursery and garden centre survey of 55 nurseries. Nursery responses were based on the perceived costs and benefits of 12 best practices (water testing for pathogens, water storage in fully enclosed tanks, water treatment facility, clean/covered storage of growing media, installation of drains or free draining gravel beds, raised benches, disinfectant stations for tools, quarantine holding area for imported plants, composting/incineration facility for diseased/unwanted plants, boot washing station, car washing station, buy only from trusted or accredited UK suppliers).

One main issue with collecting such data are the high number of non-responses when each nursery was asked to estimate the costs of installing each best practice. For most of the best practices, the majority of nurseries did not provide an estimate. In addition, the numerical responses that had been provided were dominated by a few high estimates, resulting in a skewed distribution of cost estimates. Quite a lot of the nurseries are already using some of the best practice measures, so the analysis needed to consider a baseline of what measures are already being implemented. The assumed baseline of practice included five of the most commonly used best practices – those currently used by the majority of the nurseries indicating whether they used a specific practice, or not. These were; water storage in fully enclosed tanks, clean/covered storage of growing media, installation of drains or free-draining gravel beds, raised benches and tool disinfestation stations. For the purposes of comparing the costs of establishing and maintaining the best practices with the anticipated benefits, a ten-year time horizon was selected, reflecting both the length of time before many of the best practice infrastructure would need to be replaced and the investment decision time horizon used in practice by the one nursery for which this information was available. Nursery respondents were also asked to estimate the costs to their business of a Phytophthora outbreak and (in the case of the nursery and garden centre survey) of a Xylella outbreak.

Gregory asked how many Phytophthora outbreaks could nurseries avoid by adopting best practice? This created some discussion as generally it is very hard to predict with any accuracy how many disease outbreaks can be avoided.

Q: Isn’t it better to take a measure of the price benefit of being part of accreditation, i.e. by adopting best practice the nursery can charge more for its plants than other nurseries?

A: But, if every nursery adopts best practice and joins an accreditation scheme then (apart from that associated with increased plant health/quality) there is no price advantage! It’s better therefore to stick with the data we’ve got (also given there was no time for further survey work).

Gregory suggested that if reduction of risk of an outbreak is too complex to consider at the moment (perhaps it requires a new project to address this, by looking at nursery characteristics and environmental factors and modelling the frequency of outbreaks) then perhaps we need to think in terms of how many outbreaks you avoid during a certain period until the benefits outweigh the costs? He then presented an exploratory cost-benefit analysis based on the implementation costs for the seven measures which are not common best practice currently and the perceived benefits (avoided cost) of avoiding outbreaks. Based upon mean costs and benefits, this indicated that the costs outweighed the benefits where avoiding Phytophthora outbreaks alone is considered and there are one or fewer avoided outbreaks a year over a ten-year period. As these are widely considered relatively infrequent, the analysis suggested that the costs outweigh the benefits of implementing best practice based on avoiding Phytophthora outbreaks alone. (The costs of the best practices amounted to roughly nine times the costs saved by avoiding one outbreak). However, if the potential benefit of avoiding an outbreak of Xylella was considered in the analysis, then the benefits of nursery best practice outweighed the costs if one outbreak of Xylella were avoided over an eight-year period, or one outbreak of both Phytophthora and of Xylella avoided every 9 years. These estimates were based on using the mean costs and benefits from the survey data, and assuming a 3.5% discount rate (standard in government appraisals). Considering instead median costs and benefits – which are arguably more typical of nurseries given the skewed distribution of estimates, suggested for the benefits to outweigh the costs, there would need to be at least one avoided Phytophthora outbreak every 4 years, or an outbreak of Xylella avoided every 7 years, or one Phytophthora outbreak and one outbreak of Xylella avoided every 11 years.

A further factor that could also usefully be considered is the impact best practices have on reducing risks of other pests and diseases. However, no estimates were available in the survey data for these benefits. This analysis focuses upon the perspective of nursery costs and benefits, without accounting for the costs of outbreaks in the wider environment, for example, in forest and amenity landscapes (which is the focus of modelling work by Colin Price).

There was some discussion on the costs of disease outbreaks. Nursery managers expect to lose some plants each year. What threshold of disease/mortality causes nursery managers to take action? It might be that an ‘all or nothing’ loss due to an outbreak is unrealistic and that a general erosion of loss (quantity/quality) might occur over a longer time until it gets critical.

Gregory explained that he considered this analysis to be exploratory, as risk reduction is dependent on measures implemented by the whole plant trade sector and not just nurseries. It was also difficult to get enough quantitative responses from nursery managers on costs of implementing best practice and costs of avoiding outbreaks of Phytophthora and Xylella to be confident in the analysis. Some of the responses to the outbreak questions were qualitative. Gregory concluded by emphasising the nurseries’ divergent perspectives on best practice and accreditation; some nurseries want stricter regulation and others prefer voluntary measures, particularly ‘traders’ who import many of their plants. Some nurseries adopting best practice consider other plant traders to be exposing them to unacceptable risks – an aspect that from an economic perspective could be characterised as an ‘externality’ (uncompensated effect of activities over which they have no control by another company).

For those nurseries already investing in accreditation, questions arise as to how they perceive risks and pass on accreditation costs.